"I bought the church for MoCA, and it’s magnificent."

Founder of the Museum of Crypto Art, Colborn Bell, has built a collection of NFTs composed only of works of artists who minted before December 2020. It is a symbolic blueprint and a philosophical collection based around collectivism and recognising those that participated in the digital art movement before any big money was involved.

He talks to us about building a crypto museum in an ancient church, his fight against the hegemony of corporations in the metaverse, and about crypto art as a symbol of justice and awareness that once existed in web3 but has since been lost.

What was your way to crypto?

— I started my career in a place that had a mixture of both financial and social impacts. I did six months of investment banking just to start — absolutely deplorable work — then I did two and a half years at the United Nations Capital Development Fund, building an infrastructure bank in East Africa. Then I did another two years at a wealth management firm founded by vegan Buddhists.

I was always very anti-US dollar hegemony, war profiteering, big oil, and all of these mechanisms that go back hundreds and hundreds of years. So for me, it was all about how we use capital in our existing financial architecture to effectuate change. But I found, again and again, that it was like running into a brick wall. Capital is not fluid to values; capital is actually more like cement, keeping everything entrenched. So when I discovered cryptocurrency and blockchain, this was actually capital as a fluid value transfer mechanism — kind of exactly what I was looking for.

So you saw potential in crypto to change the world?

— Accredited investor laws in the US prevent people from accessing the most note-worthy investment opportunities. So only the wealthy are able to take a risk to get the biggest rewards, and it's almost guaranteed that they will continue to see outsized profits. So for everybody else, it is almost impossible to climb up the ladder, and the idea of the American dream is totally dead.

So, I thought the ICO revolution really gave freedom of choice back to people in deciding what ideas they wanted to support and what ventures they wanted to value.

I trust code. I trust a piece of software much more than I would trust any cabal of central bankers. The rules are there in the code all written upfront. There is no inflation in Bitcoin. With the US dollar, there's 10% inflation year over year, and people are really suffering because their government is not working on their behalf.

That was my initial entrance. Then I became interested in the culture that the artists had created, the collectivism and recognition that something bigger and more important could happen here if we all partook in a new form of economy. I really liked the responsiveness with which the artists were able to inform each other of their new knowledge, new tools, new ways of being, and implementation of secondary sales. It was not about an individual artist anymore, but kind of an art collective.

And what did you like about crypto art itself that made you want to collect it?

— I think the art is symbolic of the footprint of the movement. It's just about the time-stamping that proves “I was here at this point, I witnessed and participated in this thing.”

For me, it's more about involvement than about the piece of art or beauty. I certainly make no judgments on the “quality” of the art.

Then how do you decide what art to have in the Museum of Crypto Art collection?

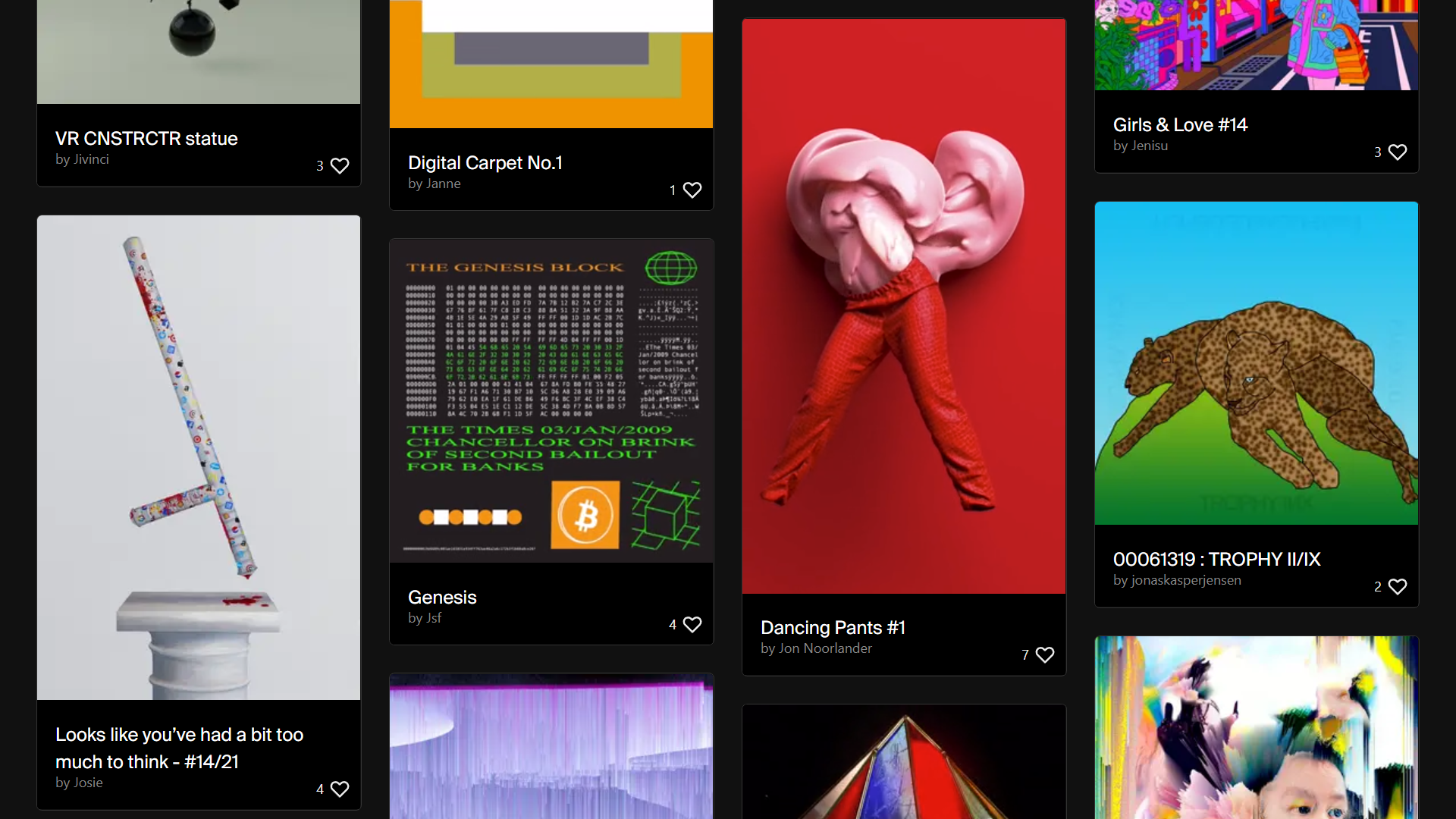

— The collection we're building is composed of one work per artist from every artist involved in NFTs prior to December 2020, when the commercial explosion started. It's a philosophical collection around the idea of collectivism and of giving everybody involved the recognition that they participated in this movement before big money came in.

We want to represent this historical period of time and celebrate what people were trying to express and put forward when there was no market for this stuff. That, for me, is crypto art.

What happened to crypto art when money became involved?

— It became something else in the sense of its philosophy.

I collect here and there, but at large, I find it totally uninspiring. A lot of people are stuck with NFTs, and they don't know why they have them. So, if we don't begin to synthesize why we have these pieces and try to flip them into some greater idea, then frankly, the only crypto art that ever existed was the initial run-up to that major sale.

I have no doubt that the most creative, brilliant people are in this space working every day. But, I think real crypto art was the manifestation of a dream into reality. Now, Bored Ape Yacht Club get spun through the Hollywood celebrity marketing machine, and a hand-drawn picture by Gary Vee goes to Christie's and sells for a quarter of a million dollars. It looks like this new NFT symbolizes the Society of the Spectacle, and if we have diluted our culture to just marketing, well then, we're big fucking losers, and we deserve everything that comes to us.

But do you hope for a better future when you will again want to buy a piece of new NFT art for the ideas it represents?

— I work every day for the future that I want to see. I don't aim to bring darkness to the NFT space, but wish to be a candle for something else. I'm not going to chase trends, push numbers to make something based on hype, or say that something is important because the market says it's important. I think artists get really hurt when that happens.

Could you tell me about the museum itself and how it works?

— It’s a nonprofit foundation. We initially raised $1.3 million in a private presale of the MoCA token. Half of the MoCA token is reserved for permanent collection acquisitions — we're mandated to create public goods for the Metaverse. There are about 12 full-time employees that work in the museum, and we are just about sustainable through the sales of our rooms – one of one unique architectural objects that leverage our curation technology to allow people to create exhibitions very quickly. Our goal is to decentralize the curatorial voice of the museum.

Beyond the permanent collection, which is 250 works owned by the museum, there is a community collection of about 8,600 artworks now. People can add up to 10 NFTs a day and use us as a curation tool — it works like Spotify.

We want to invert the traditional museum power structure so that it is not based around a top-down decision-making body that dictates what art is but instead has a ground-up collectivist approach. So MoCA is a self-sorting mechanism where people can show that they actually care about the artist’s vision and want to take on a small part in the idea of decentralizing curation.

You’re building the Metaverse art space. What is your view of how the Metaverse will develop as a part of our everyday life?

— This is a major monster battle. I think we have to fully recognize that we live in an extreme form of capitalism which is largely unsustainable and extractive. So, if we don't manage to shift our consumption preferences in digital environments, then it doesn't look good.

The potential for the Metaverse is limitless. So I don't want the vast majority of humanity to get pushed into a world that Facebook has created that will castrate their creative imagination in order to monitor and record everything that they do. This is the most dystopian vision possible.

You see the future of Metaverse as quite monstrous but still choose to be part of its creation. Why?

— There is an ingrained technological oligarchy that seeks to control and treat people as products in the harnessing of their data. Service is never free, if it's a free service, then you are the product. Corporations try to push us into meaningless consumption and tell people that they are not enough so that they have a void that they seek to fill with consumption. Thus, we're trying to build public goods for the metaverse that effectively reject this technological oligarchy.

By valuing creatives, valuing ownership and arts, and getting people to exercise their minds creatively, we will be going against increasing automation.

I recognized NFTs as a bit of a Trojan horse for opening people’s minds: questioning the nature of money, the nature of ownership, and having a macro view on AI, machine learning, robotics, and technology. By learning it, people can have more freedom in making their choices — it teaches people to exist outside the system.

This is my non-violent form of protest.

You planned to make a physical extension of the museum. Did you succeed?

— I'm here now. It's the Church of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, an hour and a half North of New York City. It was built in 1884, and it housed one of the strictest forms of Catholicism. It's 8000 square feet, and it's got incredible vaulted ceilings and stained glass. I just installed a massive 20-foot screen for projections to show art where the altar used to be, and the living quarters of the church downstairs are my home.

So I bought the church for MoCA, and it’s magnificent.

Why is it important for you to have a physical space for virtual art?

— Another idea that I've been obsessed with for a long time is the idea of ‘the third space.’

There is the first place which is home, the second place, which is work, and there used to be a third space which was generally a church or community centre or a barbershop – someplace where people could socialize and engage in their community. But, technology is pulling us into a loneliness epidemic. We lost the idea of the third space in America. Then with COVID, most people lost their second space, as they were saturated with work at home. People need to socialize, have experiences, and feel connected to one another.

So, I see physical MoCA as an open residency for artists, a broader cultural space, and a collaborative co-working space for people to meet.

Every day I wake up at 10:00 AM and work until midnight. All I do is work, and it hasn't really slowed down in this market either. However, I'm somebody that's very conscious of how my time is spent. I just think it's the highest and best use of my time, and the right moment to build it is now.