"The artist is no longer on a pedestal — he is in Discord."

Pindar Van Arman is an American artist who has created one of the most complicated painting robots in the world. Here he talks to us about manipulating atoms on quantum computers, the essence of creativity, the total freedom that blockchain brings to artists, and the unwritten rules of crypto art.

How did you come up with the idea to create robots that paint instead of you?

— It all started 20 years ago. It was a very practical decision — it was about quantity, not quality. I was a young artist, but I had to work at a day job to make ends meet. I was selling some paintings for a couple of hundred dollars, but I could not make a living out of it.

I would sell my paintings on eBay — I know some people frowned or looked down upon that — but I was just trying to find a way to get my art out there. So I thought to myself, if I could make at least four paintings and $400 a day, that would be a living for a young guy.

First, I made a robot that would help me out just a little bit, and slowly, over time, I'd add a little helper here, and there. I'd watch my kids learning to draw and have my robots imitate them.

Today, I would say that their art is at the level of an art college student, and to achieve that, they have to be one of the world's most sophisticated artificial intelligent painting machines, able to make their own creative decisions. But it got there organically, with one little improvement a month.

Do you interfere with the process, and help the robots to make the right decisions?

— It differs. Usually, I take photos of a person for a portrait myself, teach the robot what's good, making other interventions throughout. But I had an exciting experience carrying out a project called the Turing Test. It was a project for a company called Gum Gum where they commissioned six artists, including me, to make pieces of art, providing us with some inspiration and the color palette. So, the six of us made pieces of art in our own styles, and in my case, I gave every aesthetic decision, from start to finish, to my robot.

In the Turing Test, my wife sat in front of a robot and it took all the photos. My wife was sitting there, moving around, which was fun and a bit different. Then, the robot picked its favorite photo and went to work over three days; it made dozens of decisions and ended up with a very abstract portrait of her.

This project toured Europe, South America, and North America. Everywhere viewers were asked which of these pieces was made by a robot, and only 8% or so guessed my work.

What is artistic creativity if a robot makes independent aesthetic decisions?

— Creativity is when you try to solve any problem without brute force, and try to do it cleverly. We see creative algorithms all the time, and we don't even realize they're creative. A good example of creativity might be cracking someone's password. The brute force way is to try every single combination of numbers until you find the right one whereas a more creative way is to find out their birthday and try it as a key. Find out the important days in their lives and the age of their children and try to crack their past.

In this sense, my robots are very creative in trying to make beautiful compositions.

You say that deconstructing your own aesthetic process and teaching it to your robots is an attempt to understand yourself better. What insights did you manage to get from this process?

— When I want to teach my robots to do something, I must understand what I'm doing myself — and that takes a lot of insight. Sometimes I might look at a canvas and say, ‘This seems awkward to me, it's not balanced,’ or perhaps ‘the composition is off.’ Then I have to ask myself, what exactly makes the composition on?

It can't be just a feeling; you have to have some answers for a question like that. We know triangle compositions work, and that the rule of thirds works, so you start realizing that our brains also follow these composition patterns. The deeper I go, the more I think to myself that as humans, we're just generative art machines following the same rules repeatedly.

What is an inspiration, and does it matter to you?

— My early inspiration was to find beautiful things and then try to impress people with the canvas's beauty. But gradually, I became obsessed with making the robot better and more creative. Now that has become my inspiration.

So the robots are actually your art, not what they produce?

— Yes, the painting at the end is just an artifact. What I do is performance art more than painting, and it is an excellent performance piece because it has a canvas at the end, right?

Your current process uses two dozen competing AI algorithms. And you give very detailed explanations of the whole technical process on your site. Is understanding the technology or the code essential for understanding generative art?

— The final canvas has to be beautiful. That's the main criteria, regardless of how cool the algorithms and processes are behind them. No person would ever put it on their wall if it were an ugly piece of art, or a museum would never show it.

Also, when I start getting too technical, I can see in people's eyes that they tune out and get bored or lose interest. A really beautiful art project is immediately clear and easy to understand. Everyone can relate to it, and it makes them have an "aha!" moment.

What makes generative art good art?

— I like generative art, where the process by which the art is generated has meaning to the final piece. I have done this in my own pieces recently.

My newest work uses quantum computers to generate random results. Generative art in the digital age typically relies on classical computers, the ones that you and I are on. They are deterministic, meaning there's no such thing as a random number on these computers. They have pseudo-random numbers, but they're not actually random. If you use the same seed number, you'll get the exact same results over and over again. So the art is not really unique. It's pseudo unique. But quantum computers are truly random, as, with them, you're actually manipulating atoms. There is only a couple of dozen in the world, and they're very hard to access.

Where is the quantum computer that you got access to?

— At IBM in Upstate New York. It's one of the largest quantum computers in the world. They run these computers for institutions and academics for research and study. A fellow quantum artist by the name of Russell Huffman helped me get on them, and when we wanted to use the larger machines we could only work on Saturdays when no one was using them. It is also really powerful, it's not like regular programming. You write a circuit that lines up atoms and makes them interact with each other. You get some fascinating effects as you take advantage of computer superposition.

What does this mean?

— If you don't get bored, I will try to explain superposition, entanglement, and interference to you. In classical computers, the code is binary — there can be one or zero. In quantum computers, there can be one, zero, both, or any combination of every value between zero and one. I don’t fully understand it and how to take advantage of this power, but I have been told by multiple quantum scientists that these portraits look like they're in superposition.

And then, these computers have another ability, called entanglement. It means you can actually take two atoms and make them entangled, and so they mimic each other. If you measure one, you're measuring the other. If you change one, you change the other. It's not even the quantum computer doing this, it's the universe. It's something Einstein described as "spooky action at a distance," and you can see this entanglement in the pictures when there are two faces at a distance. The interference is seen when those features mesh into each other, and you see two faces that come into each other, match, and then resolve.

So, these portraits become a visualization of the technique used to make them. That's what I think cool generative art is.

Did blockchain technology bring anything to you as an artist besides an opportunity to sell your work?

— I went into blockchain for practical reasons, as I was looking for ways to sell my art. I was in the space very early on. In 2016, I did a small project on Bitcoin, but only a couple of people saw it. In 2018, I became one of the first artists on Superrare, but I must admit, it was only to increase sales.

I was just this A.I. artist that showed up on the blockchain to sell art. But, then I got into the crypto culture and unexpectedly it became a game changer. I’d been trying for almost 20 years to get into galleries, but they were ignoring me. But with blockchain, all of a sudden I didn't need the galleries. It was amazing!

I then realized that crypto is much more than this. I started doing portraits in the crypto art theme of people I knew, portraits based on people's profile pictures, and other crypto-theme-based work. It felt just as natural as celebrating the space. My Quantum Portrait series is not even on Superrare or Opensea; it's on my contract that I wrote. I finally feel completely independent.

In the beginning, I was an artist that sold using crypto. Now, I consider myself a crypto artist that uses A.I. I identify with the crypto art movement and the crypto crowd, more than the traditional art crowd. And this crowd is awesome, I love them.

Crypto artists must be their own marketers, gallerists, producers, sellers — everything. It might be really difficult for an artist.

— For me, it's a good thing. I see a lot of big artists coming in now and doing a quick drop and then getting out. But I believe that there are some unwritten rules of crypto art. One of them is that you have to engage in the community constantly, which is what makes it different from previous art movements. The artist is no longer on a pedestal. The artist is in Discord, talking with collectors and viewers and hanging out with them.

I get irritated when traditional artists pop into the crypto art space and have a quick drop. A meaningless drop that has nothing to do with crypto art and has only to do with themselves. They expect everyone to pay them millions of dollars, and then they disappear. They are like the early me; they're just here for another market to make money. That's not crypto art.

In crypto, you have to engage, and the more you engage, the more popular you become, but the less time you have to make art. So, it gives room for other artists to get as big as you. And that's a great new thing about this because you can't monopolize the crypto space.

Some artists say: I don't like talking to people — and that is fine! But these artists need a gallerist to be their mouthpiece, and there's nothing wrong with that. However, while it can work in the traditional art world, it won't work out for you in the crypto art world.

Crypto art is about being out there with the collectors and collecting as much as you're making. One of the coolest things about crypto art is how all of the great crypto artists collect themselves.

Do you collect much crypto art?

I used to spend 100% of what I made buying other artists’ NFTs. Now it's somewhere between 25 and 50% of what I sell. I'm addicted to collecting. I have a massive collection, and I'm really proud of it.

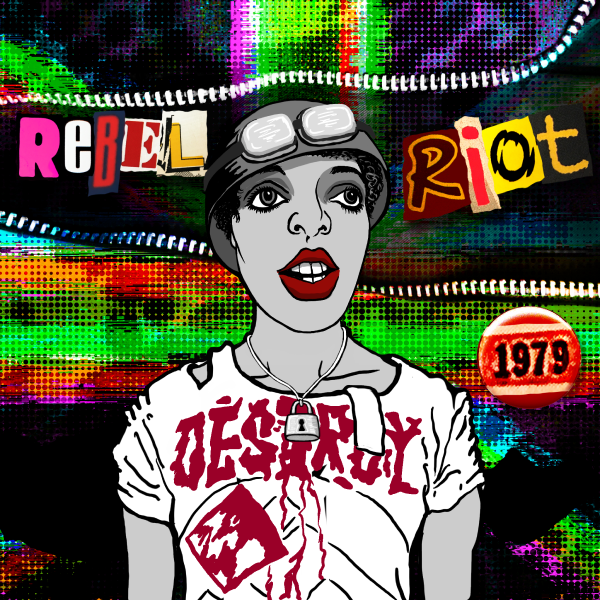

But since I have this problem of buying way too much, I have now limited myself to only collecting portraits. There are so many excellent works, but portraits are rare in the NFT space. If I didn't limit myself this way, I would be broke.

There are also several criteria for how I chose portraits for my collection. The person in the portrait has to be interesting to me. The piece has to look cool, and even better if it is a self-portrait. I love self-portraits.

You make and collect only portraits. What is it about portraits that attracts you so much?

— When you really think about it, every piece of art by an artist is a self-portrait, whether or not their faces are in them. The most exciting thing on this planet is each other. I don't care how beautiful that sunset is; it's boring when you compare it to a picture of your kids. Portraits go deep into our minds, and an excellent portrait gets behind the person's appearance and shows you a little of their personality. If I'm not making a portrait, I'm wasting my time.

And then there's a technical reason. I make robot paintings. It's very easy to make a robot painter. You can buy a floor-sweeping roomba at the HomeGoods store and add a paintbrush to it and you'd have an abstract robot painter. You could also have a perfect realist painter. You actually have one in your house already — It's called a printer. You give it an image, and it makes a perfect photocopy. Somewhere in between, there is a beautiful spot that is much harder to get to than either of those. And that's a spot where you make something that's abstract and expressive enough, but at the same time, it is recognizable.

My robots make a portrait of you, and something weird is going on with the paint: stripes and colors all over the place. You can barely see your face, but then you recognize it. It's really hard for a robot to make an abstract portrait that's recognizable. Portraits are a good test for this technology. It needs to be a very advanced creative machine. That is why it's interesting for me.

My favorites portraits from my NFT collection: